I recently went back to watch the original V/H/S after watching the most recent installment, V/H/S Halloween. And what struck me was how wild and unmanaged that first film feels. It really does live up to its central idea of videos shot by normal people that happen to contain evil things.

There’s this raw, ragged energy that the later entries in the franchise simply don’t carry. The later ones polish the edges, tidy the chaos, but here everything’s got this rough, amateurish feel to it and that seems pretty important for something called found footage.

Personally I’ve never been a big fan of the found footage genre. There are really only two kinds of people who use shaky cameras and unfocused framing: indie horror directors and creepy stalkers filming from behind a bush (usually one-handed). My main issue with the format is when it aims solely to create a sense of realism and nothing more. Mimicking amateur footage can elevate a story – but only when it’s used for more than just an aesthetic gimmick.

But the V/H/S franchise is a good example of how using a different way of filming can impact a story. As a collection of anthology films, the series takes conventional horror tropes (zombies, ghosts, demons, masked killers, etc.) and uses the unique perspective found footage offers to conjure up something unexpected. What elevates the series above the usual dross of its ilk, is that it manages to immerse without sacrificing a thing in the name of realism.

Most of the films take the form of four entries with a wraparound story in between that supposedly explains what is happening, but I’ll be damned if I ever know what it all means.

The framing story here, “Tape 56” by Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett, involves a group of petty criminals hired to break into a house and steal a videotape. These guys are utter scuzzballs – something which is a trend in this series – and just give off major ‘was once in an emo band and had an underage girlfriend’ energy. I am aware that those two things are practically synonyms.

Things quickly go off the rails when they discover a corpse in front of a bank of TVs. And either he died from intense friction when trying to rub one out to all of his skin flicks at the same time, or something much more sinister has happened.

The gang then proceeds to watch the tapes, because in horror films no one has ever heard of the concept of just leaving shit alone. Proceedings become increasingly strange every time we return to the narrative and by the end all but one of the group has disappeared and the dead guy has risen as a zombie.

As the wraparounds in this series go, this one is about as basic as it gets. It doesn’t really call on the skills of either Wingard or Barrett. But it does its job. The whole purpose these larger stories serve is to give some context, the implication being that the short films we see are the video tapes themselves and they’re somehow cursed.

To me, however, the way that V/H/S goes about setting everything up feels unnecessarily convoluted – something the series struggles with throughout. What the film is really reaching for is a long tradition of curated shock, from mondo films (shockumentaries) like Faces of Death, through seedy VHS-era compilations such as Traces of Death, and into the chaotic late-90s/early-2000s internet. The Rotten.com/Ogrish/ Live Leaks era was a cultural Wild West, where genuinely disturbing material could sit alongside banal or playful content, encountered without warning or context. You’d innocently click a link your buddy sent you, and then you’d forever have the image of some bloke jamming a jar up his arse (and it breaking), seared into your brain.

The point is that V/H/S is clearly trying to recreate the technological Wild West of an earlier era, when genuinely disturbing material could easily sit alongside mundane, innocent content. That experience doesn’t really translate to the modern world anymore, which gives the attempt an oddly nostalgic quality. All V/H/S really needs to do, then, is draw from that cultural memory — and it does, to a degree, but often in a way that feels awkward and clumsy rather than organic.

The first actual segment, “Amateur Night” by David Bruckner, is easily one of the best in the entire series. Its placing right after the 1st act of the wraparound is a little unfortunate. Because you begin to get the feeling that this series is entirely about unlikable, sleazy men. And that’s not true – its only mostly about that.

Three drunk lads film themselves trying to pick up women at a bar with a view to make a porno, a premise that could easily double as a police report. One of the women, however, turns out to be less interested in cheap beer and more interested in evisceration. Because she’s a siren, or something like.

There’s something genuinely unnerving about it – the shift from drunken bravado to corporeal horror is seamless. The camera doesn’t hold back, and neither does the horror. The gore’s great and the creature effects – which get progressively more and more overt – are awesome. Amateur Night, I like you.

Ti West’s “Second Honeymoon” is next, and it’s… well, it’s a short Ti West film. That is to say, it spends twenty minutes showing you nothing and then ends with a sudden act of violence you almost miss because you blinked. It’s fine – some people like brown bread, porridge, and the colour grey.

Next up is “Tuesday the 17th” by Glenn McQuaid. The segment follows a group of pampered teens heading into the woods, which goes about as well as you’d expect. They’re stalked and picked off by an invisible Jason Voorhees type killer. An invisible killer would certainly be a problem. However, he does actually appear on camera…sort of, his image glitches across the footage like a corrupted file.

It’s a great idea for a found footage film. And it is the first in the series that started to explore the unusual possibilities offered by the format. At least, conceptually, because in execution it’s a fairly bog standard Slasher, leaning into the campiness of films like Friday the 13th.

There are some neat twists and turns. It’s actually an in-universe sequel with one the characters having survived a previous massacre by the killer and she’s here to hunt him down. But ultimately, this promising segment comes and goes without achieving much.

Then comes “The Sick Thing That Happened to Emily When She Was Younger,” by Joe Swanberg. Firstly, what a mouthful: it’s like one those bad modern animes that have entire sentences for titles.

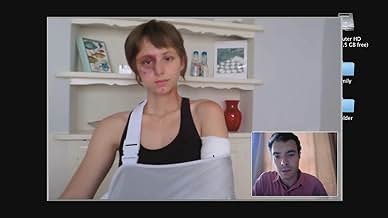

This one’s pretty unsettling because it deals with two things we all fear: being gaslit by someone we love and video calls. Told through video chats, it’s about a young woman who believes her apartment is haunted, while her boyfriend watches and offers suspiciously unhelpful advice.

Fortunately, Emily is not actually being haunted. Unfortunately, she’s actually being emotionally manipulated by her “boyfriend” and used as a fleshy incubator for aliens. What this segment does well is shrink an alien invasion down to a webcam conversation, turning implied cosmic horror into something small, intimate, and invasive.

Something which that Ice Cube starring version of War of the Worlds also tried to do last year. Except, that one was so bad you started to root for the aliens.

The final proper segment is “10/31/98,” and is directed by Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, Tyler Gillett, and Chad Villella (collectively know as Radio Silence). And after the twists and turns of the last couple of entries, this one is a lot more straightforward but far more chaotic.

A group of friends head out for a Halloween party, cameras rolling, only to accidentally wander into what appears to be some kind of cult carrying out an exorcism. They decide to intervene and save the woman at the centre of the ordeal. This good act unleashes all manner of supernatural phenomena: members of the cult are lifted up into the darkness by an unseen force; hands sprout out of the floor and walls; objects begin to move by themselves, and the house begins to actively block their escape. Because, as it turns out, the woman is possessed by a demon.

This segment’s chaotic, loud, and gleefully over-the-top. The special effects are simple and well trodden (drawing on ideas from films like Poltergeist or Day of the Dead) but effective. It just keeps building and building, and you never really get a moment to breathe until that gut punch of an ending that hits you like a train. Pun very much intended.

And that’s V/H/S. Taken as a whole, V/H/S is an uneven collection of short films that often feels amateurish, mean-spirited, but never dull. There’s an unfiltered energy to it, the sense of young filmmakers testing how far they can push the found footage genre before it snaps.

Leave a comment